A World War Two Home Front Story

Short of staff because of the war as the summer of 1943 commenced, Maryland’s Gibson Island Club (Gibson Island was connected to the mainland by a tenth-of-a-mile causeway) had so far made no plans to open either the food concession or the men’s and women’s bathhouses at the Point (the swimming area at the juncture of the Chesapeake Bay and Magothy River). Nelson Stinchcomb, my father’s age and in a middle management position at the Club, conceived the idea of hiring this thirteen-year- old as bathhouse attendant. Nelson, I should clarify, was my mentor and an especially simpatico adult. Of all those on the Gibson Island Club staff whom I came into contact with as an employee, he was by far my favorite. His son Tommy, my older brother Turner’s age, daily rode the school bus with us.

Upon completion of my 10-mile newspaper route, two hours by bicycle, I would arrive at the Point and open at 10 a.m. I would sweep both the men’s and the women’s units, clean the basins and toilets, and, as patrons arrived, hand out towels, assign lockers, and receive payment. I would close at 6 p.m. Bookish youngster that I was, I reveled in the opportunity to sit and read paperback detective novels and non-fiction on the war.

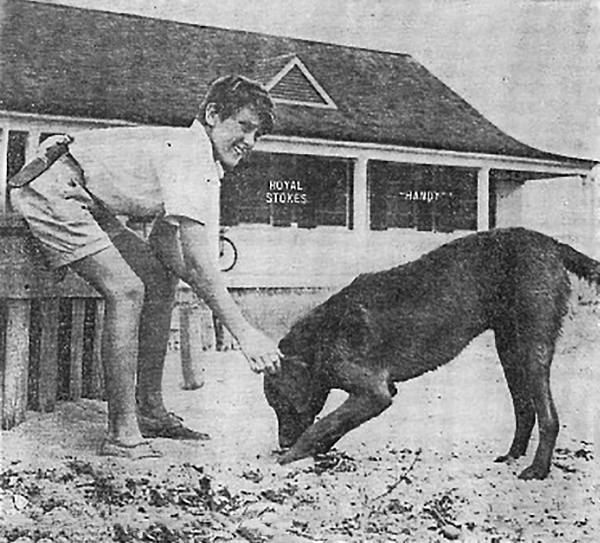

One day toward the end of that 1943 summer a photographer from the Baltimore American newspaper turned up at the Point and shot photographs of family dog Handy and me, one of which was included in a Sunday, August 22, spread on Gibson Island’s wartime activities (Victory Gardens, in particular) in the paper’s Smart Set Magazine. The caption to my photo read, “The youngsters have been as busy as the grown-ups most of the time—but youth needs some relaxation and so Royal and Handy, his canine companion, took a little time off for a romp on the beach.” No reference was made to my role as attendant of the bathhouse in the background of the photograph.

My bathhouse attendant pay was twenty-five cents an hour; my paper route paid me $5 a week. The seven-day, 70-hour workweek netted me $19 (I got a Social Security card but was too young for a Work Permit and so my pay was off-the-books and thus untaxed), most of which was banked in a savings account. Some of it was spent on 78rpm jazz and blues records. I also bought two sets of drums, the first in 1944 for $15 from my Glen Burnie High School classmate Russell Maisel (who gave them up), the second in 1945 for $75 from Avery Faulkner (who took up trumpet), older brother of my friend Winnie. (By multiplying my weekly take-home pay by 13.4, an accepted conversion figure, one arrives, in today’s dollars, at $255 a week, or $3.65 an hour, about 40% of today’s minimum wage in Maryland, $9.25 per hour.)

In a letter of the summer of 1943 to my brother Billy, who had enlisted in the U.S. Navy in January and was stationed at the Bainbridge Naval Base, Maryland, my mother writes, “Turner and Royal are working hard and we don’t see much of them,” assuring Billy, “Royal is lending you the six dollars,” and adding, “Don’t be careless with your money. You had better bring your bond home before something happens to it.”